In his writing about obsolescence and ruins, Walter Benjamin theorised that every technological process presents an utopian element at the point of its inception. As a tool in the hands of amateurs, the technological device offers a new grammar to represent reality and the opportunity to establish innovative forms of interaction. The diffusion of commercial video cameras during the 1970s brought promises of democratisation and free circulation of knowledge, challenging the hierarchy of cultural production and the passivity of viewer reception embedded in television culture. A prominent example of how these emancipatory ideals informed the creative use of video can be found in the local history of Grenoble. Between 1973 and 1976, a collective of activists and technicians known as Vidéogazette organised educational workshops on the use of lightweight video technology. Housed at Villeneuve, a socialist housing project at the southernmost district of Grenoble, Vidéogazette’s workshops sought to educate and empower citizens to claim control over their own representation. Producing a televised journal of daily life in Villeneuve, these workshops promoted an ideology of advanced democracy where viewers could become producers and, through the medium, share and discuss the social issues relevant to their everyday lives. Vidéogazette belongs to a broader context of independent initiatives centered on the idea of liberating television, and in turn liberating the means of producing information. Appearing as an aftermath of the 1968 protests, local cables offered a constellation of alternative points of view, from the community-based television programs to local broadcasts and pirate stations. A television free from state-control, and its distorted representation of reality, allowed citizens to represent themselves and project a more accurate mirror to society. Vidéogazette’s TV programs provided a space for this, presenting debates on social and political issues relevant to the Villeneuve residents and visibility for the various groups residing in the neighbourhood. Vidéogazette not only created this space but also supplied residents with camera equipment and offered courses on how to use them, with the belief that empowering citizens to produce their own information would generate greater participation in the decision-making process and accountability for one’s own context. A decentralised model of communication was later realised through the proliferation of media channels in the 1980s and 1990s. The privatisation of television and technological innovations such as satellite, digital and pay-TV drastically increased the number of channels, constituting a network of broadcasting stations that reformed the state-controlled pyramidal structure of information production. This move to the private sector multiplied news outlets, but it also corporatised the mediasphere and allowed major corporations and advertisers to increasingly monopolise information. Aspirations for social transformation through the liberation of television were ultimately absorbed into a technological utopia in which production and financial profit take precedence. New media today strongly re-affirms and expands the thematics proposed by post-68 experiments with video and television, serving as a vehicle towards direct democracy. The pervasiveness of smart devices that combine video and communication technologies allows witnesses to capture and present multiple perspectives on a single event, which are immediately shared and rapidly diffused throughout the web. Online platforms and social networks propose a scenario where information and knowledge is fully accessible, and where each of us can potentially contribute to cultural production, challenging the hegemony of corporatised mass media and political authority. These networks broaden the concept of “local communities” by connecting individuals around the world and allowing groups to form based on common interest on a global scale. While the connectivity and interactivity of the Network promotes participation and social exchange, it also fuels the production process of the new economy. As industrial labor is dematerialised and informationalised, interaction through networked communications is utilised as a form of labour that generates profit and directs marketing strategies. Social cooperation and constant connectivity are integral to work, augmenting the field of labour and blurring our public and private lives, our work and free time. The Internet realised the shift from the “pyramid” to the“network”, re-assessing notions of anti-hierarchical organisation and self-determination as principles belonging to the enterpreneurial business model. Rather than addressing a social change in terms of participatory democracy, the web supplies a supporting structure for the flow of capital and financial exchange, and advances a neoliberal ideology that supports the current mode of production and exploitation. Recently a re-politicisation of online tools has emerged in different contexts. Since 2006 WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has publicly demanded and enforced the transparency of information by publishing classified diplomatic cables and private documents from various corporations and governments. He disclosed violations and abuses by major institutions in an attempt to render them accountable to the public eye. In 2011 the world press highlighted the role of social networks to support and amplify the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and Iran. Partially inspired by the Arab Spring, protest movements across Western countries—from the Spanish Indignados to Occupy Wall Street—also emphasised the potential of online tools to spread a counter point of view, combining the communicative functions of existing social networks with the political functions of assemblies. Opposing the growing inequality and abuse of financial capitalism, these movements attempt to radically democratise how information is created and shared, again challenging centralised and corporate-funded mainstream media. As Occupy protesters chanted “the whole world is watching” in front of Wall Street last year, they reclaimed the tools to make information transparent and monitor financial power. They use social media and private networks to call for a non-hierarchical and participatory self-governed society, with the founding principle that access to the means of information production empowers citizens to participate in the democratic process. These attempts recall the initial impetus behind the Vidéogazette experiment, as well as some of the unresolved problematics. Despite the enthusiasm around the project, the commitment implied in collective organisation was too demanding and only a small number of inhabitants remained involved in the production of the programs. Many residents were not yet ready nor willing to fully engage: objections about who leads and determines the programs ultimately challenged the underlying premise of Vidéogazette. By placing emphasis on our ability to organise and engage, these counter-events raise similar issues around our role in the decision-making process, problematising our use of technologies and our position as both consumers and producers.

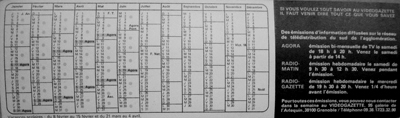

Vidéogazette (1973-1976) was a group of activists, technicians and citizens who organised a public access television program in Villeneuve, a neighbourhood located south of Grenoble’s city centre. Through weekly workshops, Vidéogazette members taught the Villeneuve inhabitants how to use audio-visual technology and produce their own television. Informed by a critical vision of industrial cinema and mainstream news media, the group sought to decentralise the flow of information and activate the role of the spectator to one of producer. One of the slogans reproduced on the Vidéogazette flyers was “wherever there is a consumer, there is a producer and a possible creator!” By taking charge of the means of information production, the inhabitants were made aware of their social context and able to play an active role in the local democracy. “Community action through video and communal experience” and a “real labour of representation with the people who are going to watch their broadcast in the evening” were common descriptions of the project. Vidéogazette was the first local television in France and part of a greater social initiative at the time. Under the mayoralty of Hubert Dubedout (1965-83), Grenoble was transformed into a laboratory of pragmatic municipal socialism, with the Villeneuve housing complex taking centre stage. Conceived as a model of co-habitation and communal life, Villeneuve (literally “the new city”) sheltered many militants born out of May ’68, as well as people of different backgrounds including Arab, Spanish and Portuguese immigrants and Latin American refugees. Villeneuve’s community lifestyle meant that inhabitants were willing to leave their front doors open, take care of their neighbours’ children, eat together, and meet every evening in a shared space to discuss social issues. Through state and city funding, Vidéogazette offered different services at Villeneuve’s Audiovisual Centre, including the production of videos, films and posters; rentals of audiovisual equipment for the locals; and studio courses for primary school students and adults to familiarise them with the equipment. Initially located in a school, Vidéogazette’s focus was on children’s education and the promotion of cultural activities. Active participation within the local social context was one of the collective’s top priorities. Learn-by-doing educational workshops allowed both children and adults to produce their own news and entertainment programs, and later broadcast these shows to the community. Screenings were often organised in common spaces such as public yards and the local theatre Espace 600. After the installation of the cabled network in 1973, Vidéogazette started to broadcast the television programs in the neighbourhood apartments. The TV programs created and reinforced a sense of shared identity, promoted transparency within news media and accountability for one’s political and social surrounding conditions. Conceived as a platform for political debate, Agora was the main broadcast program in which inhabitants gathered in a theatre-setting and discussed their opinions on social matters such as unemployment, increases in housing rent, and local factory strikes. Here different immigrant communities were also encouraged to share their local tradition by organising music performances, films, and debates on relevant issues. Some examples include “El Jerida”, a news program in Arabic, and various forums with Chilean refugees discussing the 1973 military coup. In many instances, these events were the first time the local public was exposed to thematics such as the Palestinian conflict and the dictatorships in the Latin American countries. In 1974, the collective founded the Vidéogazette association, inviting all the residents to take part in the decision-making process. Many were invited to contribute content and participate in the production of the programs. Vidéogazette members affixed graphic posters around the neighbourhood and distributed weekly programs in mailboxes in order to advertise their television and keep Villeneuve inhabitants updated. Over the years, the role of the activists increased and the subjects of the programs became more explicitly political. The idea of video as a militant tool is clearly present in a series of posters that depict a group of cameramen lined up like soldiers embracing their cameras as weapons. Among the topics presented during these years, it is worth mentioning contraceptive methods and abortion. Vidéogazette activists organised different debates around these issues, involving doctors from the local family planning association and feminist groups. These activities had a strong political connotation at the time, as abortion was soon legalised in France in 1976. Vidéogazette initially garnered a lot of enthusiasm from the locals, but after a few years only a small number of inhabitants remained actively involved. The commitment implied in collective life was too demanding and tiring for many individuals. Many also claimed that the television programs were hard to follow, and rather preferred the films broadcast on the national television channels. Only a few cultural and political groups proposed the subjects to be broadcast, leading to programs that were soon described as long talks resembling “a radio program with images.” “It’s not of interest” and “it’s just intellectuals’ chattering” were also common responses by the locals. Filmmaker Jean Luc Godard offered another point of criticism, targeting the amateur approach of Vidéogazette: “It’s not production and it’s a false idea of collective activity. They don’t have the means, and if they did, they wouldn’t know what to do with them... Not everyone can become a butcher; not everyone can use a camera [...] you need a minimum of training; you have to learn. The slogan ‘freedom of expression’ is, to my mind, a fascist slogan. If necessary, I would prefer to say ‘expression of freedom.’ But freedom is not easily expressed.” Vidéogazette ended in 1976 when the central government did not renew its financial support. In response, the collective organised a conference in Paris and distributed an ironic obituary communicating “the death of the Vidéogazette at the age of 4, due to a well-known disease called the State”. After the end of Vidéogazette, the core members of the association worked for the municipality taking charge of education and cultural activities, realising exhibitions and debates around diverse topics such as housing, environment and employment issues. In 1981, the right-wing won the local election and funding for the activities of the former Vidéogazette group was cut. As a result, many of the members moved out of Grenoble. The Vidéogazette experience belongs to the context of post-68 experimentations with video and television that reacted to the State’s control over information. This was part of a broader initiative to decentralise cultural production and redistribute governmental power to regional administrations. Until 1974 television and radio broadcasting was under the monopoly of the ORTF (Office of Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française), a state-run association that constituted five radio and two television channels in France. In 1968, strikes at the ORTF offices surfaced outrage against the government’s control and censorship of political information. According to Yves Guéna, the Minister of Information at the time, “General de Gaulle could not tolerate a situation in which television was not at the service of his policies”. The ORTF broke up in 1974 when Giscard d’Estaing took the presidential seat. d’Estaing implemented a radical reorganisation of broadcasting networks in France, dividing the ORTF’s unitary structure into seven separate companies with their own agendas and programmation. This mandate provided a significant break from the previous presidential administrations and a symbolic gesture to show d’Estaing’s liberal stance on media. Despite pressures to introduce commercial alternatives to the media sector, d’Estaing maintained the State monolopy over television. Only a minority of the French public received programs outside of the three French state-run channels—Villeneuve residents were part of this select group. Commercial channels were later introduced to France in 1981 when d’Estaing’s presidential term ended. -- Recently in 2010, the neighbourhood of Villeneuve drew in public attention when city riots broke out in response to the death of Karim Boudouda, a suspected armed robber caught in a police chase, and outrage against the representation of the city in news reports on the case. These events led President Sarkozy to pronounce the ‘Grenoble Speech’ in Villeneuve, in which he focused on issues around immigration and prejudice in the city. The Villeneuve apartments will soon set the stage for a 2012 fictional television series, called Ville9. The producers plan to incorporate excerpts from the Vidéogazette programs in the shows. The Villeneuve neighbourhood is also scheduled for major 2013-14 renovations. The plan includes the demolition of an entire tower of apartment units, formerly home to the Vidéogazette studios. Olivier Clerc. “Ghetto ou paradise? Les balbutiements de la Vidéogazette.” Le Dauphine Libere, 1 September 1975. Both positive and critical feedback from residents was often included on the Vidéogazette posters in a section entitled “Feedback.” They also broadcast television interviews in which residents offered their opinion on the shows. Jean-Luc Godard moved to Grenoble in the mid 1970’s, planning to remodel a video studio and experiment with alternative methods of production and distribution (primarily by passing out videotapes to networks of friends and associates). Here he worked with Jean-Pierre Beauviala, the inventor of the first lightweight 16mm camera and the hand-held video camera, “La Paluche”, and started to incorporate television into his practice. Grenoble set the stage for various works, including the film Numero Deux (1975) and the television series Six fois Deux (1976) and France-tour-détour-deux-enfants (1977-78). Yves Guéna, Le Temps des certitudes, Paris, Flammarion, 1982, p. 280. Speaking to local leaders of Grenoble, President Sarkozy claimed that crime was driven by permissiveness and uncontrolled immigration, and that French nationality should be stripped from any person of foreign origin who voluntarily tries to take the life of a policeman, gendarme, or other figure of public authority.

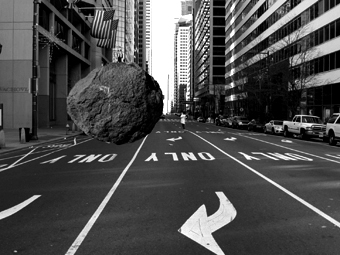

Conceived as a generative platform for collaborations, this online collection brings together artists and writers who explore the creative and critical uses of technology as a tool supporting political and social action. Invited by the curators to produce a newly commissioned work, Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, The Public School Philadelphia and Pierre Musso offer a series of essays and collective projects that address the Network both as a practical tool to organise multiple voices and a conceptual model that informs how we even think about organising. Drawing a line from post-68 experimentations with video and television to new media today, we asked the contributors to explore the re-politicisation of communication technologies in the 2011 protest movements, considering the contradictions within the technological medium. Offering a platform for discussion and debate, the Internet informed the protest movements across Western countries—such as the Spanish indignados and Occupy Wall Street—redefining the way collective space is articulated. These movements prioritise non-hierarchical and leaderless organisation where individuals directly participate in the decision-making process, and claim a political stake in the transparency of the web against the opacity of power. Creating a virtual architecture for the flow of capital, the Internet also supports the same financial system that these protest movements oppose today. In doing so, it furthers the dominant neoliberal agenda of the free market, and offers an ideal site for immaterial labour and post-Fordist production. The invited contributors responded to these issues by highlighting notions of embodiment and physicality against the disembodied and abstract character of the virtual space. This contrast points to the paradox inherent in communication technologies—on one hand they offer a set of tools to facilitate dialogue and direct action, on the other mediative devices that affect and distort our daily interactions. The image of the rock accompanying Journal of Aesthetics And Protest’s Occupy Wall Street Dispatches depicts this tension. Uncannily floating through the streets of New York’s financial district, the rock offers a symbol of protest and political struggle, as well as an incongruous physical presence challenging the abstract space of financial power. JOAAP’s inquiry into the largest “internet generation” organised protest explores the concrete characteristics that define the Occupy Wall Street experience and the practical obstacles that protesters encounter during day-to-day occupation. Contrasting the ideology of the Network with the reality of political struggles, Pierre Musso’s essay contribution criticises the illusion of a participatory democracy made possible through an internet connection. According to the media theorist, the myth of a revolution via the Network replaces and marginilizes actual attempts for social change—it fetishises technology and shifts the political to the technological. While it amplifies and broadens existing social action and public protest, the Internet does not create the conditions for political transformation nor can it substitute existing forms of collective organisation. Using an open source web platform to organise and promote courses, The Public School Philadelphia presents a series of class proposals and visual accompaniment that address alternative modes of education outside of the academic institution. They take Vidéogazette’s educational workshops as inspiration and explore ways to initiate a self-education process that allows students to re-imagine and decide how one can learn and engage.

*************************************************

JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS AND PROTEST is a Los Angeles based artists’ collective which sits at the discursive juncture of fine art, media theory and anti-authoritarian activism. Working collaboratively with individuals and collectives on several continents, JOAAP publishes a journal and organises projects to challenge hegemonic representations (of knowledge, art, activism) and spark situations for community-based social change. While they publish critical theory, they have no ties to any academic or cultural institution. PIERRE MUSSO is a researcher and theorist in telecommunications and broadcasting. He holds a Philosophy diploma and a doctorate in Political Science, and is a professor of Information and Communication Sciences at Télécom ParisTech and Rennes 2 University. He currently holds the Chair of teaching and research, «Modélisation des imaginaires, innovation et création», and is the author of numerous books including Réseaux et société (PUF, 2003); Critique des réseaux (PUF, 2003); Territoires et cyberespace en 2030 (La Documentation Française/DATAR, 2008); Saint-Simon, l’industrialisme contre l’Etat (La Tour d’Aigues, Editions de l’Aube, 2010). THE PUBLIC SCHOOL PHILADELPHA is a collectively organised school that hosts a series of free experimental courses, much of which convene at Basekamp, an art space in the city centre of Philadelphia. The Public School Philadelphia is a localised effort that is one of a number of autonomously operating schools under The Public School model. Using an interactive website for each location, The Public School operates as follows: classes are proposed online by the public; people have the opportunity to sign up for the classes through each location’s site; when enough people have expressed interest, the school finds a teacher and offers the class at a designated location.

Networks Broaden Socio-Political Action, But Cannot Replace It.

For two centuries, every “industrial revolution” has been sustained and accompanied by the construction of a large territorial and technical network. This began with the railroad, in the early nineteenth century, followed by the electrical power grid, and in turn the Internet – the latter originating from the convergence of telecommunications and computing. These large-scale industrial networks have been defined as “technical macro-systems”, in that they combine technical networks and structures of power.[1]

The “Third Industrial Revolution,” the computer revolution, which began in the 1950s, has given rise to a generalized computerization of society and the economy on the one hand, and on the other, to the development of the Internet, social networks, and information systems,[2] along with virtual and digital technologies. The new “macro-system technique” is thus made up of information, command and exchange networks, interconnected and overlapping with transportation and energy networks. The Internet is the public highway, just as the information systems of institutions and businesses are the private highways. The Web [forms] a new public sphere, rich in actions, encounters and exchanges that take place amongst a-territorialized “communities” whose interests and affinities stretch across the globe. It creates a ubiquitous and simultaneous time-space continuum of exchange and above all serves as a means of increasing and broadening activities of all kind. It is a “second world.”

In their development, large-scale, technical networks have always been accompanied by numerous myths, fictions, images and imaginary projections aimed at socializing them. Beyond the various forms the image of the network takes, depending on the technical apparatus to which it is associated, an invariant remains: namely, the fetishization of social change through technology. The schema of the network always draws from a mythological source, denoting destiny and social passage. From now on, social change will be permanently experienced by way of connection, “logging-on”, circulation and the immersion in virtual worlds and fluxes. Thus the technical network becomes both the end and means to think and bring about social change, if not the revolutions of our time. Whether it is literary fiction, futurology or socio-economic analysis of network society, the imaginative universe of the network never stops proclaiming the “revolution” of (and via) networks. This is a means of circumventing the utopias of social change, effecting a shift from the political to technology. Technology acts as a multifarious prosthesis within fragmented and disintegrated societies: communication networks take the place of social links and tools for a new direct, interactive and instantaneous democracy. This euphoric facet of the technical network, in which the latter is understood as a new universal social link, gives meaning to the activities and desires of “switched-on internet surfers,” who commune with each other in an anti-hierarchical, anti-pyramidal or anti-bureaucratic vision. This libertarian theology of the Net joins that of the cyber-corporations (eBay, Amazon, etc.) who see in the Net a “planetary marketplace” for a global and personalized electronic commerce. The political illusion of a participatory democracy (“e-democracy”), made possible via an Internet connection, is another aspect of this technological religion.

This is, however, no more than a revival of the “old” technological utopia mounted by Saint-Simonian engineers at the beginning of the nineteenth century when the first modern technical networks, the railway and telegraph, began to appear. The Saint-Simonians hyperbolized network thinking: “To improve the means of communication […] is to establish equality and democracy. The effect of the most perfect system of transport is to reduce the distance not only between different places, but between different classes.”[3] The geographical reduction of physical distances – if not the interchangeability of places – though communication channels is equivalent to the reduction of social distances. The modern cult of the network is born.

This myth, established around 1830, continues into the present day. It is even revived with the advent of each new technical network: one can think of Lenin’s remark that electricity defines socialism in associating it with the power of the Soviets; or again, the telephone, followed by Internet, considered as society’s “nervous systems.” Thus in the mid-1990s, the Vice-President of the United States, Al Gore could declare before the international community: “the President of the United States and I believe that an essential prerequisite to sustainable development, for all members of the human family, is the creation of this network of networks. To accomplish this purpose, legislators, regulators, and businesspeople must do this: build and operate a Global Information Infrastructure. This GII will circle the globe with information superhighways on which all people can travel […] And the distributed intelligence of the GII will spread participatory democracy […] I see an new Athenian Age of democracy forged in the fora the GII will create.”[4]

This mythology of the network – which I have named elsewhere a “retiology”[5] – willingly presents itself in the form of a utopia, a harbinger of a “new world.” Six “markers” characteristic of recurring discourses on the network can be identified. The first and oldest is associated with the network and the body – in particular, the network and the brain. In this sense, the Internet is seen as a “planetary brain,” the producer of collective or collaborative “intelligence.” The technical network is repeatedly compared with a human organism or one of its parts (the bloodstream or nervous system) by way of metonymy.

The second marker suggests that the network can be formalized in its correlation with a hidden logic or order. The Internet is thus presented as a decentralized network, halfway between a centralized audiovisual network and an integrated telephone network. The third marker is the most powerful: the technical network heralds a social revolution through the breakdown of existing social structures and the promise of a new “modernity.” The forth marker sees in the network a contribution to peace, prosperity and universal association, in that it forms an artificial coverage on a planetary scale; this is, for example, Manuel Castells thesis of “informational capitalism” and “network corporations.”[6] The fifth marker: the network brings economic prosperity, progress, new riches, the multiplication of new services, a “new economy,” etc. The last marker allows for social, political or organizational alternatives within the very architecture of the technical network: horizontality versus verticality, decentralization versus centralization, the network versus the pyramid. Here again, the network supplants the political and replaces it within technical choices.

To decipher the ideology of the network does not mean criticizing the use of network technologies. Rather, it is a question of shedding light on them, without confusing technology with the socio-political realm. Such a critique is in no way incompatible with the recognition that the Net and social networks serve as means to communicate and expand traditional, political and social action, as a number of recent uprisings have shown. It does, however, allow us to avoid reducing the “Arab Spring,” or other popular movements, to simple “Facebook revolutions.”

Indeed, the uprisings in Arab countries have been qualified, notably in the North, as “Internet revolutions.” This slogan is based on a few symbolic images such as that of a veiled Egyptian woman brandishing a computer keyboard during demonstrations in Cairo. Thus, the keyboard is understood to have replaced the flag. Wael Ghonim, a young Egyptian, Google’s head of marketing for the Middle East, created the Facebook page “We are all Khaled Said”, the name of the young man tortured and beaten to death by Alexandrian police in June 2010. Having arrived in Cairo to take part in a demonstration, he was arrested by security forces. Ghonim himself described the movement as “Revolution 2.0.” As events took place, the various “Arab Spring” movements were labeled “Internet, Twitter or Facebook revolutions” or again, “Cyber revolutions.”

But the question remains, to what extent the “socio-political impact” of the media, information and communication technologies (ICT) and social networks have contributed on these popular movements. Two diverging theories confront each other: either their role is marginal, or even nonexistent in relation to economic and political “rudiments”, or conversely – and this is the dominant theory in Europe and the US – the increasing use of networks is the cause of these revolts.

To accept the first theory is to deny the social innovation associated with the use of ICTs; to retain the second limits the analysis to a technological determinism, or further still, to “techno-messianism”, to use the term coined by the anthropologist Georges Balandier. Without long running social, political and cultural movements, there can be no revolt, and even less a revolution. Should we not remember that many revolutions have taken place without the Internet and that the Iranian “Twitter and Flickr revolt,” in 2009, ended in failure, while the Iranian authorities recovered photographs of the demonstrations as a means of enforcing repression? Indeed, the Arab uprisings were not the first to use social networks or mobilize demonstrators via Facebook. In February 2008, social networks were used to protest the FARC in Columbia. Likewise, in Italy, on 5 December 2009, the Popolo Viola movement gathered at least 350,000 people against the politics of Silvio Berlusconi for a “No Berlusconi Day.” Again, these movements had difficulties sustaining themselves and attaining a genuine political goal, whereas in Tunisia and Egypt uprisings led to the removal of leaders from power.

Inspired by the experience of the Arab Spring, the peaceful protest movement OWS (Occupy Wall Street), which in 2011 denounced the abuses of financial capitalism, was particularly active on the social networks and rapidly spread throughout the US. Yet, beyond the protest itself – or more precisely the revolt of the “outraged” – the movement did not give rise to a genuine political solution.

It is thus not possible to believe in an intrinsic revolutionary power of “social networks,” unless we adhere to the slogan announced by Google’s CEO: “The goal of the company isn't to monetize everything. The goal is to change the world. We start from the perspective of what problems we do have,”[7] The theory of “Facebook revolutions” is based on the belief that a medium such as the Internet is capable of transforming public protest into a social and political movement, in the same way that traditional political organizations such as political parties, associations and labor unions do. The expression of general unrest in society always takes place when popular movements take to the streets, but a watchword, leader, parties, unions and other organizations are necessary in creating the conditions for a revolution.

Conversely, we cannot ignore the role ICTs have played throughout the Arab Spring. In the space of thirty days, Tunisia, for example, where the wave of uprising began, underwent a total upheaval. During the revolt, which began in the country’s rural region, the Internet enabled the spread of unrestricted information, provided by Internet users themselves. Interpersonal communication, via telephone or SMS, relayed the message, while television satellite networks, in particular Al Jazeera, allowed information to be broadcast abroad, countering official state propaganda.

To avoid lapsing into simplistic explanations that seek to establish a linear, causal link in terms of the “effects” or “impact” of technological innovation on social processes – as if technology acted on the social from the outside – or conversely in refusing to take into account the innovation of the Internet, it should be understood that ICTs are no substitute for any other phenomenon, whether it be political parties or labor unions and other forms of social organization. Hence, Hillary Clinton, commenting on the Arab Spring, could declare: “The Internet is freedom!” – thus transforming technology into a symbol.

On the other hand, communication networks are a factor in the, spread and broadening of real activities, no matter what form of social and political action these activities may take. For all forms of technology allow an expansion of being and a broadening of human action.

*************************************************

In the context of of The Whole World is Watching, we are presenting our Dispatch project. The project stands as a journalistic effort to capture the zeitgeist of Occupy Wall Street. It also aimed to contribute to the organization of the consciousness of the participants in Occupy Wall Street (OWS). Inspired by Freirean notions of popular education(*) we understood the early stages of OWS as a significant site for popular education. We mean that the social void created by the “economic crisis” was not to be filled by a ready-made political or cultural organ but was partially being forged in the collective process of Occupy. That process was comprised of meetings, teach-ins, arguments, structured dialog, workshops, learning-by-doing; popular education. Dispatches was our attempt to organize research from within the movement to report on and further this process of education.

It functions like this; researchers use self-generated questionnaires to collect particular snapshots of the psycho/social dynamics within Zuccotti and other Occupies. This data is disseminated for future movement use. Cross-currently, by canvasing the crowds with cogent questions, we provide a theoretical framework of shared investigation to help facilitate dynamics within the immediate occupations. The act of interrogating dynamics of internal processes, of opening up internal dynamics to constructive investigation is very important.

Included in this online document are: an initial rubric provided by Ultra-red which we distributed to the researchers, the theoretical background of the project, and dispatches by Mark Read (Occupy Wall Street), Barbara Adams (Occupy Wall Street), Sarah Lewison (Occupy Carbondale) and Irina Contreras (Occupy Oakland).

We understand the relationship between media and movement to be contextual. The Dispatch Project met with our interest in networked media because of the relationship to context- Dispatches aimed to reflect back crowd generated knowledge at a very particular moment. The project formed less than two weeks after Occupy Wall Street began. At that moment, the debate as to whether OWS needed a set of demands and the questions of form and style which ran through the movement were still flowing hot. We imagined the Dispatch Project as a creatively pragmatic response to these mediatic debates. The Dispatches would internally highlight the dynamic antagonisms encountered in the occupations which were central to their growth and provide a way to further the dynamics. Context-less media pretends to clarify with clearly messageable points. Such media reports univocally, “Protesters at Occupy Wall Street stands for the reinstatement of the Glass-Steagle Act.” instead we imagined the Dispatches might say stuff like, “we are really encountering our own class assumptions and we just need to speak to more people to work through it, and here's how we've managed to work through it so far...” answers and questions aimed towards facilitating the needs of a growing movement.

* We began considering Paulo Freire's work in earnest after reading

Luis Genaro Garcia's Reclaiming Inner-city Education (http://www.freireproject.org/blogs/reclaiming-inner-city-education%3A-public-art-public-education-and-critical-pedagogy-social-and-)

Ultra-red's contribution to issue 8 our our magazine, Andante Politics, Popular Education in the Organizing of Unión de Vecinos (http://www.joaap.org/issue8/ultrared.htm)

View this essay for more background on the project: Common notions, part 1: workers-inquiry, co-research, consciousness-raising

Marta Malo de Molina (http://eipcp.net/transversal/0406/malo/en/base_edit#redir)

*************************************************

A rubric for Popular Education Movements that help us investigate the conflicts and tendencies from within.

Ultra-red

Many of us in Ultra-red have taken much inspiration from Freire’s Education for Critical Consciousness (which covers the “generative words” phase of the thematic investigation) and Pedagogy of the Oppressed (which covers the “generative themes” phase of the thematic investigation). There is also the shorter essays in his Cultural Action For Freedom. But none of these are online resources. What IS online is a copy of Marx’s own Worker’s Inquiry(1880).

Here is a very rough list of questions that could be asked about the practice of a popular education thematic investigation. Obviously, there are many resources for conceptualizing and developing such a process. But these could be some questions for getting that process started. Ultra-red offer these out of total humility, respect and in solidarity with the beautiful comrades there in New York.

1. How have you practically organized yourselves for existing day to day?

2. What forms of mutual teaching have you organized?

3. What have you learned through that teaching so far?

4. What questions have emerged in the group from the mutual teaching -- i.e. questions or limits to the group’s understanding? Perhaps those questions or themes name points that the group holds in common or, very importantly, they could be points that mark differences or even contradictions within the group.

5. Has the group developed any sort of analyses of those questions or themes, even if provisional?

6. Have you been able to articulate any actions or long-term investigations to pursue those questions or themes?

7. What are the practical obstacles for the group conducting an investigation? What are the strategies for changing those obstacles?

8. What are the protocols that organize the direction and experimentation in the investigation? If there is more than one inquiry, do all of the investigations use the same protocols or is each inquiry developing their own?

9. According to your analysis, who are other specific political struggles that you want to learn from? What is the strategy for extending an invitation to those struggles to join an investigation with you?

10. How might others who are not able to join you physically practically participate in your investigations?

*************************************************

Notes from the Periphery — Barbara Adams

This morning I woke up and, after making coffee and checking email, I went to Facebook. There were a number of posts from people expressing sadness over the death of Steve Jobs and there were a number of posts from yesterday’s protest as part of Occupy Wall Street. The odd thing is that these posts were from the same people. The fact that someone can simultaneously critique corporate culture and laud the innovation at Apple is not as strange as it might at first appear. As much as the movement might seem dualistic—‘them’ (the 1%) versus ‘us’ (the 99%)—there is an effort to avoid binaries and their oversimplification of identities and values. By not packaging the demands or branding the effort, the protesters have created an opening. What began as a small crack is being pried wider and wider each day. This lack of closure—no end goal, no time frame, no limit on who might participate—is enticing in the way that small opening in a construction wall offers a glimpse into what’s being built inside. There is clearly something under construction and people want to see what it is. When I questioned people milling around the square over the course of a few days, most told me they came because they “wanted to see.” One participant told me she came to see for herself on the first Monday of the occupation and has returned every day since that first visit. She, like many, envisions herself as part of the periphery. She chats with people, she listens, she marches, but she doesn’t perceive herself as part of the action—she sees herself as someone who supports the real activists. This was perhaps the most intriguing theme that emerged from the discussions I had with people—that many don’t feel like equal participants—rather, they understand that there is a core group and a surrounding periphery. The language conveyed this clearly and there was consistency in how these people identified themselves as “supporters” rather than full-fledged actors. This periphery sees the core as those people who are sleeping in the square, speaking at assemblies, facilitating committees, and regularly interfacing with the media. Based on the limited conversations I had, there seem to be a few different reasons for distancing one’s self. For some, this is a learning period. They are waiting. For now, these people are content to just be present and watch. Certainly they do more than watch—they help out when needed in the day to day functions of the square, they march and participate in the larger events—yet, they are waiting until they are comfortable with the protocol, language, and new types of personalities (one young woman’s description) they encounter. For others, they feel like activists from another time and place. These people were active on campaigns with a sharper focus than this movement and engaged in resistance with a clear ‘enemy’ with the belief that issue-by-issue, action-by-action, the world could change. They are not naïve. These activists know that today they confront a hydra, a chimera—not a lone dragon to slay. Because they recognize this, they know the tactics need editing, updating. These people are on the periphery as they weigh and assess their knowledge alongside the practices being deployed at the occupation. Again, there is a waiting period. A third group on the periphery is comprised of people who are trying to decide if they agree—either with content or with process and in some cases, both. These people are reluctant to fully commit because they are ambivalent. What is interesting is that many of these people are not necessarily concerned about deciding one way or the other—they are content to remain undecided. A number of people told me they need not negotiate their position with the larger group, instead choosing to engage only from a distance and when comfortable. Through observation I witnessed the assumption that people are aware of protocols and methods of communication and organization practiced by the group. This was visible at the square, on the march over the Brooklyn Bridge and at the march in alliance with the unions. However, what is interesting is that this did not seem to alienate people. I saw evidence to the contrary. When people were confused or unclear what was happening, they asked strangers. Throwing people into this setting and assuming competence seemed to make that ‘competence’ (for lack of a better word) happen. It is certainly the case that the occupation is a constellation. The infrastructural layout and structural organization of meetings and activities attests to this. However, this constellation is overlaid with concentric zones—a core, a periphery and, perhaps, a semi-periphery. How people are assembled is blurrier than any model. For instance, during the day at the square you see almost as many people with notebooks, cameras, microphones, clipboards, questionnaires, and so forth, as people without. The lines here are fuzzy. A student working on a research project is also part of the action. Some journalists I spoke to consider themselves professionals reporting on the occupation while also participants. The researchers and reporters are not objective bystanders, but are often subjective allies and actors. Some of my students confirm this, as does the testimony of a group of (mostly European) journalists with whom I spoke. I had some exchange with members of the Spanish contingency. They began meeting for assemblies in May to discuss how to internationalize what was happening in Barcelona, Madrid and other cities in Spain. Their group joined forces with Greek activists, 16 Beaver, the May 12 movement, Bloombergville participants, and other groups in August. This initial group, according to one participant, “melted” into the larger group and was one of the seeds that sprouted into the resulting occupation. A couple of days ago around lunchtime, I ran into my friend Wendy. She was at the square with a group of community college students in one of her sociology classes. After chatting with Michael Moore and encouraging her students to mingle, she left for her other job. As she walked away I heard her say, “Now I’m gonna go get something to eat and really be a part of this.” Yesterday at the march with the unions and students, a man approached a friend and me. He said, “Glad to see you smiling. Seems the older folks are the only ones with a smile. The younger folks are so serious. They don’t know how long we’ve waited for something like this.”

*************************************************

Rubric Questionaire with Antonio — Barbara Adams

Excerpt from a discussion with Antonio (organizer): What is learned through the sharing and the opposition of ideas?

Strictly speaking on observations from the Internet Committee: I see two camps of people who share: Camp A has already the “solutions”, camp B is willing to explore and is open to sharing various ideas. The Camp A that has the “solutions” usually cannot see out side of their “solution”. In tech circles “solutions” equal goldmines, so a rigidity to a single solution equates to buying stock in one company.What are the limits to learning? To critical approaches, generally?

Limits are contextual, and maybe in retrospect can they be understood. The context here is always evolving. To call a limit of learning now would be to premature.What points are generally shared? What are the points of contention?

Points that seem to be shared are the problems with efficiency. Solutions are contentious. Therefor I’m trying hard to look beyond this binary.Has there been effective analysis of those themes (the differences, shared elements, contradictions, and so forth)?

Not really, many people think that looking outside of the problem-solution binary think that doing so is actually detracting from the problem-solution!!!What are the thought blocks that you have experienced?

I hit blocks when the idea of multiple or parallel solutions are infinite! It boggles my mind.And what have you done to overcome these obstacles?

I always fall back on chance. But it never looks good. When some one ask how did you choose this or that, you say you picked a number out of hat, your are considered not scientific etc...What are the protocols/values/ethics that organize your participation? Other people’s? If more than one model, how is this being reconciled?

Above all I place “openness towards variation” high on my list. Many people get stuck in trying to change people. I don’t want to change people. Ultimately my participation is limited by time. I’m not sure what guides other people.How are different groups with different interests coming together/collaborating? Or how are they divided?

It’s hard to tell. Its too complex for me to work this out. Many networks are operating on many levels.What would you say you’ve learned?

I’ve learned that...“The price of freedom is eternal vigilance” - who said that Thomas Jefferson? But now I am asking myself, does it have to? How can system have built-in freedom(s)?Do you think the occupation follows a script for resistance that’s been handed down, or is the occupation reworking this script via improvisation, negotiation, and so forth? Are new ways of communicating, of being together, etc. being forged?

I think we can also learn a lot from histories. Unfortunately many younger people think that it is boring, and that somehow we are at a different place and time, that we’ve made progress. Additionally they have don’t even know that there are many histories, as we’ve only recently been teaching this idea in our schools. (I could be wrong!)

I think the occupation thinks it’s all new, and they are playing unique roles. Maybe the rules have changed and the results are different, But like I was saying before, this resistance is part of human history, maybe even at the core of natural history. Sometimes I think it’s cyclical.

*************************************************

Week 1 through Week 3 Occupy Oakland Dispatch — Irina Contreras

Overview

Ogowa/Oscare Grant Plaza

Ogawa, which has been re-named Oscar Grant Plaza is slick with rain. There appear to be around 40 tents max. The ground is soggy and some people have arranged their camp so quickly that they don’t even have a tarp underneath or above their tent to trap the water. My partner and I laugh at the haphazard nature of it all.

Zine Table

We wander looking for a place to plug in to what is happening. I decide to check out the infotable to see if I might be able to help provide literature. There are several zines in very short stacks that someone from a distro may have been able to provide. There is a zine about Barcelona General Assemblies and very limited materials as far as international movements are concerned with. The zines sit on a makeshift wooden crate that looks like it might not make it through the night. A tarp has been created by plastic tubes with some plastic over it. I take notes and decide which of my favorite things to xerox at work and bring. In the end I make a few copies of special items writing on the front “rare zine from 94 Chiapas uprising about Compa Ramona, please share or bring back when done”. They are all taken within two days and I figure or hope someone must have really liked them.

Food

We also stop at food to survey what is there and join the food meeting. It appears that the group is with varying levels of experience and doesn’t have an actual chapter of Food Not Bombs involved or anything of the sort. I realize that someone is actually attempting to fix their camp stove while we are meeting with a lamp on their head. He holds a lighter and a few other objects that I cannot recognize in the dark The group is about 15 or so of us and no one can hear one another very well at all.People take cardboard from the water donations to sit on top of the wet ground.

Facilitation

There is a facilitator that seems to have a general lay of the land but occasionally relies on an older fellow with a Slingshot Organizer. He is writing notes in his organizer while he lays on his stomach. He is obviously not cold and gives advice about how to best set up the food for everyone. He seems to me to be fairly incoherent though when asked a direct question, has a specific number for everything. There is one tent and one cardboard box with pans that a fellow brings during the meeting. People are so happy they cheer. Mostly, there are 4-6 24 packs of arrowhead water bottles and some tea on a table. There was coffee, which is now gone.

Preparedness

As a group, we are fairly unprepared and it is within these first 24 hours that I realize how unprepared. I realize from a personal perspective that I “used” to have a tent and some camping equipment. No more... Some people seem to have a lot and for the most part, things are shared. Large family sized tents are donated the next night by Lupe Fiasco as well as more cooking and camping equipment. Additionally, within the next 48 hours of Week 1, while we are not prepared we make for it in quick response. It seems to me that this our strength. We may not have much but we are quick and resourceful. We know how to respond.

It’s always easy for me to think of food so I will use that example. By the time I come back after work on Day 2, food is in abundance and in fact a full stocked kitchen is in place. There is an actual pantry with vegetable and dry goods sections. Between Day 1 and 3, The sinking and smooshy ground is covered with hay (also donated) in its most problem and high traffic areas and with a pathway of wood boards that are actually adhered to the ground running parallel to the sidewalk and wheelchair accessible pathway.

*************************************************

Week 1 through Week 3 Occupy Oakland Dispatch — Irina Contreras

Week 1 Day 2 Participants have divided into groups like: logistics / facilitation / media and tech / food / safer spaces / security / child care / art and entertainment / outreach and education to name just a few... In addition, a POCQPOC (people of color and queer people of color) Caucus is formed starting the first night at Occupy Oakland with around 30 people attending the first night and leading up to around 80 people at the end of the week. The group is amidst the decision of becoming an official committee or staying an informal group of people of color involved to support other pocqpoc nationally that are encountering severe racism in the Occupy Movement. In response to my involvement in the POCQPOC caucus, some friends and I decide to bring our discussions and concerns to the general afternoon participants holding an informal discussion around decolonization. Part of what interests us is in our inability to talk about articulately even amongst each other. We come up with the 3 questions and points of reflection that are negotiable upon the collective group. 1.) What is colonization? What happens during colonization? What does colonization look like in our day to day life? 2.) What does decolonization look like? What could it look like? 3.) What are ways that decolonization already exist in our families, communities and cultures? The discussion proves to be one of the most informative times I have spent in the last three weeks. I am floored in how I hear people speak in different ways in which they feel “stuck”. There are several of us and while we all come from different backgrounds, geographies and classes, one person who sat down to eat with us is a young white male. He tells us about how broke he is and how he lives with his girlfriend. He is ashamed he says and feels strongly that it makes him part of the 99%. No one disagrees with him but he struggles to articulate the privilege in which he does carry with him. Before long, there is some frustration. As facilitators, a few of us intervene in hopes that the conversation doesn’t revolve around him and the disagreement but it does. Before long, one participant of color has spent their time around several minutes to try to help him understand. Later on, another participant and I are thanking everyone for the discussion. I say thank you to him and he comments “I hope I didn’t ruin it. I felt like an agitator.” I tell him he wasn’t and I was honestly feeling that at the time. Later on, when I check in with people they agree that we need to think more carefully about how even informal conversation takes place in public space because they feel we spent our time looking at only that. I feel frustrated, engaged and yet wonder why I didn’t necessarily feel that way. If there is anything that is pointed out, it is that we hardly know how to speak to each other. It is sad and yet profound to me. It is around this time that I begin to feel disengaged with the General Assembly process and realize that part of my strength is what I can bring to the other circles or to the other committees/subcommittees. General Assembly seems to be a time in which colonization rears its ugliest head. For example, when the discussion arises of having a powerful speak-out against police brutality organized by folks who have long been a part of the struggle in Oakland, it is met in the GA with discomfort and fear. At 33 years old, I feel very conscious of what I can give and what I cannot give. I do not want to give to that process and I feel entitled to not give. I know that my feelings will change but in order to keep myself physically coming, I shut off when I hear people say that the event around police brutality is violent, divisive and they don’t understand. Much between the first few days and now (beginning of third week) is a blur.

*************************************************

Week 1 through Week 3 Occupy Oakland Dispatch — Irina Contreras

WEEK 2 When we began to receive notices during Week 2, preparations went under way immediately. Gas and flame stoves were supposed to be taken away and then somehow brought back or never really left. I would like to say that we prepared properly for the evening of the October 25th Raid and Attack, and yet I know that we didn’t really in many ways. The walkways and planks I spoke of were pulled out (dispatch 1) to pass inspection. Any items of importance, for the most part, were taken away. Our altar in front of the POCQPOC tent stayed-marigolds in place until the pigs smashed them. Most of the children are taken home as well as elders, some houseless folks and our peoples with mental health struggles or concerns. People who have historically lived in Ogawa/Grant Plaza stay for the most part. If there is one thing that Disoccupy Oakland has been successful at besides responding quickly, it is ( perhaps more importantly) that people have been fed regularly and adequately without question. People have been given clothes and basic need items that the city does not. In the fall of 09, I was one of those people that called the Food Bank of Oakland to get emergency food. I got a call 3 weeks later with a message that said “Oh, I hope things worked out....”. The homeless population is vast and intergenerational. They are young and old and my age. Outside of my Food Not Bombs days as a teenager and young twenty-something-er, it is the first time that I feel a sense of that “wall” being broken. During FNB, I have always felt they knew that they were doing charity work besides the fact that we gave them shitty food (Guerilla FNB, I am NOT talking about you) and with Grant/Ogawa, if I serve food it may be to anyone that I serve. And if I am to receive food, it may be anyone giving it to me. Yet there are still many security and safer spaces issues around mental health and race that are troubling, to say the least. There are several incidents in which “Security” only replicates the daily violence experienced by poor people of color or of the poor and addicted say of the Tenderloin. When there is an incident, people will rush to see what is happening. Sometimes, it reminds me of high school during a girl/cholita fight. Other times, elders step forward to de-escalate and intervene. There are self elected “security” that become more like the People’s Security. These self elected tend to be people from Oakland generations deep that know everyone and challenge “Security” from Occupy. At least twice, Oakland Police Department is called because people say they don’t feel safe at the camp. Right before the raid and attack, I spend some time talking to folks in Security about what I can do/who I can send from our group to make sure we can change things. This is one way that “organizing” works best at Grant/Ogawa- you come and you sit in open space and look for people you know, and talk to them. I find myself sitting in hay sometimes in my stupid work clothes doing this to build relationships. One thing strikes me while I am sitting one day: security person comments about a man who is standing near the Barbecue line. “That man has been eating all day....he hasn’t moved”. Another person from Food walks by and says “he is hungry and he has been hungry....we are gonna make sure he gets full”. On the other hand, the tension is thick in the air the night before the raid. Things are uncomfortable and have become quite, dare I say.....anarchic. Groups of crusty youth have joined the camp and are fighting. Other folks are high and doing hard drugs giving some to the kids. There are reports of girls being assaulted and/or turned out. Knowing a youth affected, I am scared because I have been that young girl sleeping in a squat knowing I might wake up with someone on top of me. When I wake up, it is not a person but our BayAction Text Messages all coming in late (as they have been doing in half of the city) telling us that the camp has been raided/people have been arrested and taken etc. We head to downtown to see if it is possible to retrieve anything at all, even things from our altar, our whiteboards for meetings, our tent...anything....Police are everywhere, Oakland’s tank is parked on 14th and there are paddywagon’s as well. Tired cops line every possible entrance and exit and we make out a cop chanting “We are the 99%” with a snake march wrapping around Telegraph. We wait for the march and realize it’s mostly upper crusties who have probably run out quickly as well as some media. As we walk away, I look at the barricades and realize that they have used our own wood that we used to make accessible routes on the dirt. It’s hard for me to not think of DF where tourists everyday go to look at the ruins that are built upon the ruins upon the ruins. I get coffee and head to work to call NLG.

*************************************************

Occupy Carbondale Illinois — Sarah Lewison

Occupation and Popular Education or How the National #Occupy Movement Lifts All (local) Ships November 2011 Quite soon after Occupy Wall Street erupted as a presence in Zuccoti Park and our consciousness, people in Carbondale Illinois began to discuss its local relevance. This is a geographically remote area, where there is a great forest and rolling hills covered with orchards, and factory-fields of corn and soy. There are also many people who are unemployed or barely making it in their small businesses. The larger factories in the region have mostly closed or have gone to where labor is cheaper, and the only expanding industry now is coal mining. This is home to generations of working class people whose labor brought wealth to the cities; farmers, miners and factory workers. Today the largest industries, however, are in education, health and service work. In Carbondale, Southern Illinois University (SIU), an Illinois State public research university, is the largest employer, followed by a hospital, another health care provider and then Wal-Mart. There is a high rate of poverty, many live month to month on social security, food stamps and part time jobs; the many check cashing and instant loan stores on the highway that passes through town attests to this. Carbondale and the Southern Illinois region are ideal places to build power among the 99%. This is also, however, a place where people tend to keep to their own neighborhoods and beaten paths, and where it is people likely feel more comfortable going to Wal-Mart than to the Interfaith Center where Occupy Wall Street meetings were held. Early on, The Occupy Carbondale meetings had a good showing of students, educated middle class and trades people, and even a couple of individuals who lack housing and other essentials. At the second meeting the assembly agreed, through consensus, to occupy a grassy location on the campus that faced a small state highway. Target: We have no obvious symbol to occupy here; centers of power are not visible. Big banks don’t even have branches here; they just collect our bills and mortgages thank you very much. The state does funnel money into the region through the University, however, and occupying the campus was a strategic way to support four bargaining units of employees who were in the middle of a long-term labor dispute. A Specific issues: While the signs people made for the occupation site spelled out the broad demands of Occupations across the US, at SIU, we were on the verge of calling a strike that might stop the university in its tracks. It was a perfect time to learn about the stakes that management was playing with in their pursuit of a more corporate education model. For one, the administration showed they were willing to publicly pit student fees (a crucial student concern) against faculty bargaining rights in order to, as they said, “make ends meet.” This helped bring students and faculty together to recognize their common desires and sympathies. Although the labor dispute and the Occupation had their own trajectories, the existence of each made the other a little more possible, and freed people in both camps up to speak to the connections. As for the labor issue, four units of the Illinois Education Association (IEA); the Graduate Assistant Union (GAU), the Association of Civil Service Employees (CSE), Non-Tenure-Track Faculty (NTT) and the Faculty Association had been working without contracts since summer 2010. In the spring of 2011, the administration forced us all to take unpaid furloughs and then attempted to impose similar mandatory furloughs as a permanent fixture in the contract. In summer, the Administration made their“best and final offer,” negotiations came to a halt. The university wanted sole authority to furlough and lay off employees (tenured and not) in the event of financial emergency without any oversight or transparency. Basically, they did not want to reveal what they were doing with the people’s money. Although there were four units in negotiation, the most complicated demands were directed at the faculty who were pressured to relinquish shared governance over issues like online course offerings and work load, matters usually addressed at the department, rather than the Chancellor’s level. We knew that the Chancellor was making over $350,000 a year, so it was hard not to imagine that paring down on admin side of the equation wouldn’t solve some of their fiscal“crisis.” Their terms were arbitrary, and because they had treated all units with equal disdain, it was clear the school was trying to break our unions. Organizing: For a couple of weeks, we didn’t know if we would strike or not, as each unit had a separate ballot and timeline. Meanwhile Occupy Carbondale was in a second week of full-time presence on campus. New people joined, non-students who had long been waiting for such a moment of public dissent. The fall weather was lovely and graduate teaching assistants brought their classes to the occupy site, professors invited activists to speak in their classes. These activities lent a counterpoint to students’ concerns about the strike, as they encountered other young people who were building new vocabularies to describe the predatory nature of corporate economics at the school, in the nation and in their own lives. When the weather turned bad, Occupiers pitched tents, and although the university administration had tolerated the camp thus far, campus police chose a bitterly rainy day to seize and destroy the several shelters and tents. This awkward move on the part of the university strengthened local support and brought more people to the two General Assemblies which were held daily. Once a TV journalist came to do a story, and ended up doing most of the talking; “we in Southern Illinois have been saying that’s just the way it is for much too long,” he said. The next day, university security threatened to suspend and arrest people caught sleeping- because of “health hazards,” and so sleeping was moved across the street to private land, and people took healthy 2-hour shifts standing by the road in the brisk cold and rain to maintain the 24/7 occupation we had committed to. Preparing for action: All four units voted to strike, yet there were anxious days between balloting and setting a strike date. Finally November 3 was chosen as the day as that day. Negotiations were to continue until midnight the night before, leaving room for a settlement. That evening, all units met at a former high school to rally and make up picket teams. As many of us university workers are separated on a daily basis by our offices, departments and responsibilities, it was exhilarating to become visible to each other in such a huge assembly. It was also a surreal scene; the high school’s power had been cut, we were gathered in an enclosed outdoor yard, illuminated by halogen construction lights mounted on a portable crane and powered by a generator. Strike!: Later that night we got word that three units had settled and the faculty had been isolated. Bright and early the next morning, we headed out to picket lines with our signs- faculty and supporters clustered at all entrances to the campus. People from other units joined us as they could, but they were also obligated by their agreement to work. A vicious editorial in the only daily paper called us privileged brats for daring to challenge our work conditions in a down economy, ignoring the fact that salaries were not a critical item on the table. We didn’t know if we had public opinion behind us at all, and it was evident from the emails the Chancellor sent that she was determined that university “business” would go on as usual. We were Told we were dispensable and that our numbers were insignificant, it began to feel like this would not end quickly. The editorial continued on, suggesting that some of us might die before this strike was resolved. Because the health of the university is tied so closely to the local economy, the reactionary tide could have risen against us. This, I think, is where the Occupation movement helped redirect the conversation in our favor; by keeping the truth of our class relations in the foreground. Picketing is a strenuous physical activity; you are standing in the elements, often by the road where people might challenge you. It is monotonous work, made easier only by the fellowship of colleagues and the acknowledgement of people passing by. Picketing makes the invisible worker visible, and puts her into the public eye. I think that our public presence triggered memories of regional labor disputes from the past, in which communities survived because of their staunch solidarity and morale. I think that the working class people unconnected with the university made the distinction that the people standing on the street corner with picket signs were much more like them than those who were managing the university. And as we stood on the corners, postal workers, electrical workers, and others with and without union representation, with and without jobs, came by to bring us coffee and support. Restaurants donated food, and each evening, our striking body gathered together and shared a meal and stories. Solidarity, Victory: Students came by daily to tell us that classes were not going as usual, and that they wanted us back. Many picked up signs and joined the lines, shouting, “We want our teachers back!” Others made work about the strike and the Occupy movement. Still others went on strike themselves; heading back to dorms for a respite from the semester’s inhuman pace. After the first couple days, two undergrads used Facebook to invite students to march on campus with faculty. The third student rally led a huge crowd of students, faculty and supporters to surround a building where the Board of Trustees was meeting, people involved with Occupy Carbondale did a mic check. That evening, the Administration and our FA negotiating team came to an agreement that gave us the transparency and accountability we wanted from the university. No furloughs without third party oversight, and no arbitrary layoffs. The next day we went back to our classes. While not all students had participated in the rallies, for many, it was their first experience in raising their voices together with others to make demands, and they had the delicious satisfaction of winning. Soon after the strike was resolved, bad weather arrived and students went home for Thanksgiving. Occupy Carbondale decamped from the school at that point and moved to the building that housed an erstwhile Indymedia Center. From here, the desire is to continue working to catalyze and involve people in Carbondale and the larger region. In conclusion, the convergence of our strike and the occupation movement worked to strengthen people’s solidarity and identification with labor, and its successful resolution, I think, presents a challenge for us -university workers and Occupiers- to start learning how we can better support the struggles in the wider community.

For a good article about the strike see Adam Turl’s piece in Socialist Worker online: *** Video of dental hygiene students protesting: *** A rally in the woods: Whose University? Our University! *** Creativity! *** and one more for good measure: *** After-rally solidarity singers. 11/8/11 : ***

This website is presented in conjunction with The Whole World is Watching, an exhibition curated by the Session 21 participants of the École du Magasin at MAGASIN-CNAC, 3 June – 2 September 2012.

Download the press release here.